Our Very Own (1950) is like opening up a time capsule and seeing the world as it was in a year that began a new decade, that oddly seems at once to look ahead bearing unconscious predictions—and, also, to take a brief glance over the shoulder at a world that was about to be relegated to memory and snapshots. This film is about a teenager who discovers that she was adopted, but it is not about adoption. It is about belonging, about losing one’s identity and finding one’s place in the new thing called the nuclear family, which would play such an important part of our national identity in the 1950s and ‘60s.

This is part of the Fabulous Films of the '50s Blogathon sponsored by the Classic Movie Blog Association. Have a look here for list of other great blogs participating in this event.

This is also a continuation of our year-long series on the career of Ann Blyth. I’m going to talk about pretty much the entire movie. So get comfortable. If you have any objection to spoilers you should leave the room. It’s also going to be a really long post, probably one of my longest ever, so you’ll have to stay overnight. I’ve changed the sheets on the bed in the spare room and cleared some space for you in the top drawer of the dresser. Supper’s at six.

The film is produced by Samuel Goldwyn, and I have read references made about it being a tale of an idyllic family in suburbia somehow related to the Andy Hardy films over on the MGM lot. But I disagree. This movie is really more closely related to Goldwyn’s other films like The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) covered here, where returning servicemen come home to a world that is both familiar and yet strange, and it is also a cousin to I Want You (1951), covered here, which also features two actors from Our Very Own: Farley Granger and Martin Milner. That is a film about a family and community dealing with their men on the precipice of the Korean War.

Our Very Own falls on the timeline in between those two movies and between those two wars, and being a linchpin for those films and the past and the future is what makes this film so very interesting.

Ann Blyth, top billing here, stars as the teen who discovers she was adopted, and that her adoption has been treated like a family secret. Unlike some of the other troubled young women she had played up to this time in such films as Mildred Pierce (1945), Swell Guy (1946), and A Woman’s Vengeance (1948), she’s a good girl here, a model daughter, poised, mature, far less mercurial than those other girls, and her strong sense of self is almost a metaphor for her confident and comfortable post-war world—that will be shaken to the core by something so small as a birth certificate.

Miss Blyth, 21 when she made this movie, wasn’t done playing teens—we’ve already covered Once More, My Darling (1949) and Sally and Saint Anne (1952), and in none of these films is she ever playing the same person. We recognize Ann Blyth from film to film only in her beautiful face; everything else is different: her acting style, her reactions, her body movement, and, as we’ve noted repeatedly, her voice. Did her beauty make some overlook the subtle power of her acting? Compare this to a megastar like Bette Davis, whose larger than life characterizations were punctuated with bold makeup and wigs, but whose strong personality, familiar gestures, and that just-a-girl-from-Lowell, Mass. stage voice never changed.

Ann Blyth worked from the inside out, especially in this role.

We begin tantalizingly with the arrival of a television delivery truck to the family home, our first symbol of the 1950s. It is being delivered by Farley Granger, and the youngest daughter of the house, played by Natalie Wood starts us off by telling us bits of important information: first, that deliveryman Farley is the boyfriend of the eldest girl, played by Ann Blyth. Natalie teasingly infers that Ann has competition for Farley’s affections from the middle girl, played by Joan Evans. This will lead to conflict and be a major theme of the movie.

Ann is turning eighteen years old this spring and is about to graduate from high school. Joan is sixteen years old and she is chafing under the dominance and the importance of an older sister to whom all sorts of wonderful things seem to be happening. Joan is suffering with the middle child syndrome. Natalie Wood is about nine years old, being seven years younger than Joan Evans. That age difference is only briefly brought up in the movie, but more importance should play into it because Joan had been the baby of the family for a long, long time. Finally usurped by Natalie Wood, making her suddenly a middle child, should be a big part of her resentment.

Though Ann’s trauma at discovering she was adopted is the focus of the movie, this is really an ensemble piece, and we find that the event affects everybody in the house.

Mother Jane Wyatt, with her Eastern finishing school accent that tells us right off she is a lady, is kind and gentle and sensible, and has a strong position in the family. She decides, for instance, where the TV is going. The most important decision of the day. She is the one who manages the girls. She is the one who organizes the birthday party for Ann. We see that her relationship with her husband is a good one. They are partners and equally supportive (unlike we’ll see later in Ann Dvorak’s character). This is important because, unlike many teen angst movies that would surface in the 1950s, the children’s problems here are not more important than the parents’. The parents are not background props. The family is all in this together.

The opening scene is quite funny, and Natalie Wood is a hoot as the talkative, pesky little sister. While Farley Granger climbs up on the roof to put on the antenna (remember the forest of antennas when we were growing up?), his assistant, played by Gus Schilling is inside trying to assemble the cathode ray tube into the cabinet. TVs did not come in a box from Best Buy. They were brought home like a new baby, revered as an altar, and we see how the TV instantly takes over this home. Gus is hounded by Natalie Wood. She is genuinely hysterical, always underfoot, always questioning him. At one point she discovers among his tools a razor on the end of a handle and innocently thrusts it under his neck, asking, “Is this a razor blade?”

He gulps, his carotid artery nearly a thing of the past, and sarcastically replies, “Yeah, why don’t you go out and play with it.”

Author Suzanne Finstad in her biography on Natalie Wood, Natasha: The Biography of Natalie Wood, notes, “Jane Wyatt and Ann Blyth felt there was something very touching about Natalie, an ‘endearing quality the camera captured. As Blyth, who had been a child actress remarked, ‘You can’t teach that to someone. That is something that owns you, and she had that ability.’”

Author Suzanne Finstad in her biography on Natalie Wood, Natasha: The Biography of Natalie Wood, notes, “Jane Wyatt and Ann Blyth felt there was something very touching about Natalie, an ‘endearing quality the camera captured. As Blyth, who had been a child actress remarked, ‘You can’t teach that to someone. That is something that owns you, and she had that ability.’”Natalie, herself a megastar by the end of the decade, warns the rest of the family who arrive one by one, to stay away from Gus because people watching him make him nervous, and then she stays to watch him and hound him with more questions. She is his new buddy, and he wants to kill her.

I love when that old familiar test pattern comes up on the TV once poor Gus finally cranks it up and gets it going. Later on, when color TV came out, test pattern changed and it wasn’t half so interesting looking. The first program that comes on, naturally—the fights.

(I remember the days of sitting in front of the TV early Saturday mornings with my twin brother with our bowls of cereal waiting for the broadcast day to begin. We were early risers, and inevitably, the first thing that came on was the test pattern with that high piercing tone. We sat there stoically watching it. The sad thing was we were actually entertained by it.)

Farley Granger is referred to by Gus as “boss.” We are not told that he owns the TV store and repair shop, but he is in a position of responsibility. He puts Gus to work, and in another scene he uses the van to take Ann to the beach, so he evidently has permission to use it. He is not a high school boy. He is in his early to mid-twenties. He has a job and he is serious about Ann Blyth, and we see that her mother is serious about him.

Farley brings her home before curfew because he wants them to see how steady he is. Though he’s always grinning and teasing Ann, easy-going and affable, he is a mature guy who displays concern for her welfare at various points in the film, so we know that these two are probably going to be married, even if they’re not talking about it yet.

The role is decidedly different from the brittle, edgy, angst-ridden roles he played so beautifully in other films, and we can imagine this part was not much of a challenge for him. However, Farley Granger’s confidence, especially his stunning virility, cast a strong presence in this film that really helps us to see he is not merely an appendage of Ann’s teen social life; he is probably her future. His being mature makes her more mature also.

Jane Wyatt remarks that she likes him, and considers him “suitable,” noting to her husband that she herself was seventeen when they married. It is one of many clues to coming-of-age in society at that time. Though Jane Wyatt is not brokering her daughter in marriage, many young women did marry early, even well through the 1960s. It’s one of the reasons why we had the Baby Boom. Moreover, we are not told that Ann has any intentions for college and we are not told that she currently has a job, or is looking for one. She, like many girls at the time, may be considering marriage as a career.

In any case, this was an age where young people looked forward to being adults, of leaving their childhoods behind, which in and of itself might be a mind-blowing concept for people today in their twenties and thirties, forties, and even fifties. Today it is more common for people to want to stay young, perpetually, perennially young and to this end some people feel that behaving immaturely is a step toward that goal and seemingly try their best to be as immature as possible. It was not always so.

Farley works all day and he gets sweaty, and when his workday is over, he puts on a suit and tie and takes his girlfriend to a party. He does not change into sweatpants and a T-shirt (play clothes) and spend the evening playing computer games. We are less mature, and we need toys.

This may be a criticism, but is not meant to be an indictment of our present-day society. I wouldn’t want to regress to the 1950s for many reasons. It’s important when we look at old movies, as we’ve mentioned before on this blog, to take them as they are, in their setting. Some people will look at an older movie, including Our Very Own, and call it dated. To call something dated is to dismiss it, but the very fact that this movie is dated makes it valuable. To be sure, directors, writers, actors, producers did not make a film with the intention of having it be timeless. Having no premonition of what DVDs or VCR cassette tapes would be, they did not make their movies for the future. They made them for the present; even TV residuals were unknown in the late 1940s.

Our Very Own is irresistibly, and importantly, dated, and so it gives us a wealth of material to study.

Middle girl Joan arrives home riding in a jalopy with a bunch of friends from high school. One of them is our old favorite, Martin Milner, a strapping young lad so sweet, but so indignant that Joan appears to have a crush on Farley Granger. In that next film we see them together, I Want You,both Farley and Martin are drafted into the army. Farley draws the lucky card and ends up being sent to Europe, but Martin goes to Korea, where he is killed. The Korean War is the fate that lies ahead in some way for these characters in Our Very Own too. Martin Milner is only sixteen in this movie. When it’s time for him to graduate, the Korean War will be in full flush and he will be of draft age. Of course, they didn’t know that when they made this movie. It was made and released before Korea. It’s only because we can look back with hindsight that tells us even more about this movie that they knew when they made it.

In I Want You, Farley regrettably leaves behind his beloved jalopy when he joins the army. And we see the teens in this movie have their jalopies, souped-up, made over cars from the 1930s. It’s funny that when we see movies or TV shows that are made today that are set in the 1950s, the teens are driving cars like a 1955 Chevy or 1956 Ford, but those would have been brand-new cars back then. Most teens would not have been able to afford them. Most teens would be driving late 1940s cars, if they could afford them, but a lot of them, drove cars from the late 1930s. There were no cars made in the early 1940s during the war because all car manufacturing was suspended. So we see Joan Evans and Martin Milner and the gang drive up in a souped-up pre-war car. Ann Blyth’s best friend, played by Phyllis Kirk (in her first movie), however, stands out because she drives a brand-new Cadillac convertible, paid for by her wealthy dad.

I get a kick out of the scene at the end of the party when the all the kids jump into their cars parked all up and down the street, rev up their engines, honk their horns, and peal out. The neighbors must have loved that.

When Joan gets home, after a perfunctory greeting to the newest member of the family, the TV, she climbs the ladder up to where Farley is working on the antenna and flirts with him a bit, in full notice of Ann Blyth. She’s not sneaking around with Farley behind Ann’s back. She seems to want needle Ann. Though Ann tenses up, she does not accuse her sister outright of being out of line because the scene is really quite ambiguous, and because Joan Evans has a clever passive-aggressive tactic that makes her the winner in these exchanges. She soothes big sister’s feelings just enough to keep Ann off balance, and that will make her full-out attack on Ann later so unexpectedly cruel.

Ann, the oldest girl, is poised, kindly, and self-confident. She’s the leader of her two younger sisters, a benign and benevolent leader and is sure of her place in the family this spring when she is turning eighteen and graduating, both of which make her the most important person in her family right now. And she’s got a gorgeous boyfriend. Any of this, let alone all three, would be enough to drive a kid sister nuts.

Farley arrives to take her out for the evening to her friend’s house party. Troublemaking Natalie Wood, who doesn’t have a vengeful agenda like Joan Evans, she’s just mischievous, insists the couple take Joan with them (she’s hoping to create a scene) and Joan is ready to hop up and go. Jane Wyatt, sensible mom that she is, puts a leash on Joan and sends Farley and Ann out to be alone together. In this step, she reigns in her younger two girls and further bolsters Ann’s importance in front of everybody.

We see immediately that Farley’s a good guy, because even though he doesn’t want Joan along, he generously offers take her. He's a good sport about Joan’s flirting, which he does not take seriously, because he is mature and too manly to have his head turned by a sophomore.

With the younger girls sent to bed, it’s telling that the first program that the grown-ups want to watch appears to have dance music. In those early days, most people thought of TV as radio with pictures. I like the way Jane Wyatt strokes and scratches Donald Cook's upper arm as they talk.

When Ann and Farley come back from the party, Joan spies on them kissing on the porch. (Love Farley’s rattled surprise at being discovered.) Joan, in Ann’s absence, has put on one of Ann’s more grown-up dresses to model before a mirror. She wears it out onto the porch to purposely interrupt the couple, and flirts pretty shamelessly with Farley. Ann, not happy about this, confronts her and Joan backs down good-naturedly, reassuring Ann that Farley’s not interested in a kid sister. Once again, this passive, smiling retreat from Joan mollifies Ann, whose generosity is spurred again and she gives Joan the dress.

But Joan’s retreat is temporary, and something unexpected happens that gives her needling of Ann a little more teeth. Joan wants to get a summer job, and needs her birth certificate in order to prove that she’s sixteen years old, and legally able to work. I get a kick out of her use of the expression “pin money,” a phrase used probably since Jane Austen’s time. It seems an anachronistic term for the 1950s, but then, these girls don’t have to work. “Pin money” indicates their small wages would be blown on Cokes and movie magazines. They have a comfortable home, built before the 1950s suburban tract home explosion. Their parents employ a live-in housekeeper who’s been with the family since they were first married. The family is able, we assume, to get by well on their father’s single income. Their mother probably does not work outside the home, except perhaps engaged in civic or charitable causes that have her coming and going. Notably, they are a two-car family.

Jane Wyatt and the family housekeeper, played by Jessica Grayson (in her last film, unfortunately, Miss Grayson would die in 1953) are getting ready for Ann’s eighteenth birthday party. They are setting up folding card tables and getting out dishes and plates, and they are very busy. Joan pesters her mother for the birth certificate and Jane Wyatt tells her that it’s in a box in her desk. Joan goes up to her parents’ bedroom and finds her birth certificate, but sees another envelope that is clearly labeled as Ann’s adoption papers.

Now, if I wanted to hide adoption papers, I wouldn’t label the envelope “adoption papers.” I’d write “Last Month’s Gas Bill,” or “Uncle Charlie’s Gold Fillings,” or “My Secret Plans for World Domination.”

Neither Ann, nor her younger sisters know that she was adopted. Joan is shocked, and flustered at now being a keeper of this very secret information. She can’t un-know it. It’s there in her mind, festering and it’s going come out sooner or later.

I love the moment when Jane Wyatt, downstairs, still fussing over the party preparations, suddenly realizes that Joan might see the adoption papers upstairs. She lifts her face towards the ceiling, a quick jerking movement, a look of horror, an ominous chord of music, and we know she knows that she just did a really dumb thing, a potential for tragedy.

Jane runs upstairs. Run, Jane, run. Daughter Joan, though a flurry of nerves inside, plays it cool and doesn’t let on. Jane discusses it with her husband when he comes home and we get the plot exposition that they always meant to tell Ann she was adopted, but decided not to, then the years just passed by. Mother Jane says an interesting and poignant thing, that whenever her daughters squabble amongst themselves, “I think about it.” There is a fear stabbing her that acknowledging her daughter is adopted will tear her from the family.

Joan Evans plays her role well. She’s not really a mean kid, but she’s got growing pains and there is only two years difference between herself and her older sister. Two years can mean a lot when those years are sixteen and eighteen.

When school lets out the next day, the day of the party, Ann and Farley Granger head to the beach for a quick dip and the idyllic summertime spot for romance. He takes her in his TV repair van, and she changes into her bathing suit in the back of the van. These are the footloose and fancy-free days of finding a secluded spot on the beach without 1,500 other people around.

And this very stunning and distinctive bathing suit was such an eye catcher, apparently the government of Chuvashia, a republic of the Russian Federation, decided to put it on a postage stamp.

The beach scene is sensual (Ann is gorgeous and Farley’s a knockout) and very romantic. Here we see their grown-up attraction for each other and guess that they will be together forever. This is not malt shop stuff. They are both sexy. They are grown-ups. They look like grown-ups. They talk like grown-ups. The music they listen to on the portable radio is not rock ‘n roll. More on that in a little bit.

She rests on his back, rubs her chin on his bare shoulder blade, while he strokes her arm and kisses it, and they talk about the future. She writes words on his back in sand. When they come out of the surf after swimming, there is that lovely moment where their wet bodies embrace, they kiss each other, the ocean rolling a magic carpet up to their toes. A moment to rival the passionate beach scene in From Here to Eternity, the waves come in and roll around them on all sides. I wonder how long it took to set up, because it’s a great looking shot.

At the time, a syndicated column by Gene Handsaker noted that Ann Blyth had “cut her knees, soles, and ankles on the rocks in the surf when on location…” Ah, ugly reality.

When Ann gets home, happy and glowing from being kissed by sun, and sea-spray and Farley, we see Joan looking at her intensely. “What?” Ann asks, amused.

“I was just wondering how it would feel.” Ann thinks she means what it’s like to turn eighteen. But we see that the information Joan has uncovered about Ann’s adoption has been working at her, playing in her mind. What had shocked her only a few hours before and seemed something forbidden and unthinkable, now is all she can think about. It’s fascinating to her, but she’s not at the point of wanting to use the information as a weapon. It’s just that she’s the first one in the family to start considering what it means to belong and what everyone’s place is.

That is really what the movie is about, not whether a child is tainted by adoption, or whether adopted children should be told much sooner that they are adopted. Certainly, if Ann had been told as a young child, she would not be having this crisis now—but then we wouldn’t have a movie.

And despite whatever superior attitudes we may have about our more open society, people still keep secrets from their children about parentage under many circumstances, and discoveries inevitably lead to crisis.

At the party that evening, all her school friends are wearing dresses and jackets and ties. Listen to the music they’re playing on the 78rpm records. We are in the last days of big band dance music. When younger people think of the 1950s today, they may have an image of Happy Days in their heads and rock ‘n roll, but that didn’t start happening until 1955. What is now called the American Songbook of pop music still made number one on the hit parade charts until the end of the decade. Hit Parade. The TV show killed by rock ‘n roll was still playing American Songbook music. Rock ‘n roll came very late in the game, and that was something for kids, not young people who didn’t want to be thought of as kids. Natalie Wood, by the time she became a teenager, would be turned on to rock ‘n roll. But that wasn’t for her big sisters Ann and Joan.

I get a kick out of them singing “Happy Birthday to You” for two reasons. One, because they appear to be doing it live, and it’s a nice sound with everyone singing together, and many of the voices are not that great. It sounds very natural, not stagy and we hear Natalie Wood’s, enthusiastic child’s voice above the crowd.

The second thing is “Happy Birthday,” is, I believe, still actually a copyrighted song, so most of the time that’s why we see in movies and TV people singing “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow,” to avoid paying royalties.

I love Martin Milner’s unenthusiastic rumba. He cracks me up in this movie. Many decades later, he reunited with Ann Blyth in an episode of Murder She Wrote, which we covered here.

So much attention paid to Ann is driving Joan to her worst impulses. She is rude to her sister, flirts with Farley, commands his attention, and when his cufflink gets snagged on her dress while dancing, she drags him out on the porch to be alone with him. Mama Jane Wyatt is on patrol, pulls her aside and gives her what for.

Ann is furious, but she is controlled because she is the older sister. Those who are privileged must set examples, but when the party’s over, Ann has a showdown with Joan. The middle child angrily blurts out the secret that Ann is adopted.

Here the movie suddenly changes tempo, it becomes a somber, darker piece. A warm family comedy has flipped into something sinister.

Her parents, at first, step in and handle the explanation very delicately and not in a melodramatic way at all. They reassure her, saying all the right things, that she was chosen by them, that she is special to them and that they love her. She takes it all quietly, and absorbs her parents’ words unquestioningly. It’s a lovely scene, Mom and Dad sitting on each side of her, each holding one of her hands, murmuring calm and comforting words.

But when she leaves to go to bed and thanks them for throwing her the party, there is a formality in her politeness that brings Jane Wyatt to tears because it’s happened, she’s just lost her daughter.

Ann walks into her bedroom like a zombie and looks around, but everything is somehow changed. It’s like she’s entering her room for the first time, looking at the walls, the birthday presents left on her bed, her student desk where she does homework. She’s wondering who she is. She takes the locket off that her parents gave her for her birthday, because there seems something artificial about it now. Her trauma is not simply suddenly discovering she is not related by blood to her family, but that the news of it came to her as a hateful taunt, and that it was kept a secret from her, which in her mind validates that something unnatural and sinister has occurred, that she has somehow been betrayed.

A poignant moment when Natalie Wood, who evidently has overheard or been told the turmoil, knocks on Ann’s door and wants to come in to talk, but big sister Ann is off the clock to younger siblings now. She gently replies, “Not now, baby. Go to sleep.”

The family dog, however, gains entrance, because apparently the secret password is “woof.” Besides, Ann needs to hug somebody, preferably somebody who won’t talk and ask questions.

The dog was called Melinda in the movie, but the actor’s real name was Rags, and he proved to be a Method actor whose need for motivation held up shooting. According to a syndicated article, Rags was supposed to lick Ann’s face in this scene. Unlike a lot of other actors who’d performed kissing scenes with her, Rags seemed to dislike the taste of her screen makeup. His trainer “solved the problem by rubbing her cheek with a chunk of beef, and Rags’ performance was enthusiastic.”

Rags’ big love scene must have ended up on the cutting room floor, though. And it never led to Max Factor or Maybelline putting out a line of beef-flavored foundation or concealer.

The next morning, Natalie Wood wants to be reassured by her parents that she herself was not adopted. Joan, in the doghouse, feels terrible for what she did, but her parents have forgiven her and they keep reiterating that everything is normal, that nothing has changed their love for their children. But something has changed the equilibrium, in their sense of who they are in the nuclear family.

Jane Wyatt became an expert on how we perceive the nuclear family, and was quoted about TV’s Father Knows Best: "Each script always solved a little problem that was universal. It appealed to everyone. I think the world is hankering for a family. People may want to be free, but they still want a nuclear family."

Jane Wyatt, not so coincidentally, was chosen for role as the mother in Father Knows Best, because of this movie. She would win three consecutive Emmys for that show. The producer of the show met her on set during filming of Our Very Own and remembered her when it was time to make that television show.

At the time she did Our Very Own the role of the mother was not exactly something that Jane Wyatt really wanted to play because once an actress started playing mother to grown children, that was all she got. However, doing this movie proved to be lucky as it would bring her a series, giving her a regular gig for six years. Also, working in movies around 1950 got a bit dicey, particularly for politically liberal leaning actors. Jane Wyatt was put on Hollywood’s infamous black list. She had publicly denounced McCarthyism, and was one of the Hollywood group who traveled to Washington, D.C. to protest the congressional hearings. The 1950s was not as placid an era as the Silent Generation would have us believe. There was a lot going on under the surface, a lot of cracks in the foundation, but Miss Wyatt rose above it in the nuclear family.

Mother Jane goes up to Ann’s room to have a quiet talk with her about the situation. Ann is brooding over her typewriter, stuck on a speech about citizenship she has to make at the graduation ceremony as the vice president of her class. Ann asks about the circumstances of her adoption, and we learn that her birth mother lives about an hour away. The term “birth mother” was not used commonly at this time; we hear the phrase “real mother” and though it may seem somewhat insulting and incorrect to us, I think it lends a wry irony and a punch to the story. Ann is somewhat wooden with her mother, still having a hard time swallowing the news, and unthinkingly insults Jane by inferring that Jane is not her real mother, and wants to meet her real mother.

Jane forgives her, but also fires back a verbal slap with, “You’re only feeling what I’d want any daughter of mine to feel about her mother.”

Ann’s birth mother is played by Ann Dvorak. Not married at the time of Ann’s birth, and Ann’s father killed in an accident around that time, so the baby was put up for adoption. Ann Dvorak is now married—happily or unhappily, or just resigned—to a different man named Lynch (there’s that name again) who knows nothing about his wife’s having had a child before he knew her. She does not want him to know.

We get a whole lot thrown at us to mull over in the Ann Dvorak scenes. Her husband wears the pants in the family and has her under his thumb. We don’t see that she’s crazy in love with the guy, just that she’s got a roof over her head and she feels lucky to have it. Miss Dvorak does the Stella Dallas bit, the bad blonde dye job, the frumpy body padding, ill-fitting clothing a bit too loud, and speech that smacks of a lack of education. She lives in a run-down bungalow on the other side of the tracks. We hear the huff of a freight train, the track in the foreground, see a rundown 1930s car chugging down the road, the air pierced by the wailing of a baby.

When Jane Wyatt goes to visit this forlorn neighborhood, in her tailored white suit, white gloves, the tails of the scarf tied in a band around her hat draped down her neck, she looks immaculate, like a memsahib making a charity call at the hut of the rubber plantation workers.

The film is fortunate to have Ann Dvorak in this role, as the part walks a fine line between genuine pathos and cliché. We are meant to understand, as Ann Blyth will come to understand, that her being raised in a “nice” home is better than being raised here, that she was lucky to be adopted by “nice” people. But Miss Dvorak’s work is so strong that we take her character as more than a type, she becomes someone truly tragic. It’s a powerful, heartbreaking performance as a brittle, sad, overwhelmed woman, who chain smokes her way through a couple scenes that show us first, that she’s curious about meeting her daughter, and second, that her daughter must be kept a secret from her husband.

As much as she gets a kick out of looking at the photograph Jane Wyatt shows her, as impressed as she is to know a daughter of hers is graduating from high school—she does not want this girl in her life. There’s no place for her. That ship has sailed. “It was just one of those things,” she says of her pregnancy. But she agrees to let Ann Blyth come to visit her if she comes on a night when her husband is out bowling.

One of the things I really like about this movie is how atmospheric it is. We are in a warm late spring. The director, David Miller, sets up shots that give us such a strong sense of place. The glow of faces under a porch light emerging in and out of shadow. A glimpse into the house through the screen door. Two sisters standing in the upstairs hallway late at night.

The sultry evening when the family eats their supper out on the patio, seated at a round table, and the camera slowly pans around the family circle, morosely quiet, stealing glances at Ann, all on pins and needles because after supper, Ann is going to visit her real mother. You could cut the tension with a knife. Ann is irritable, snapping at her parents because she is so nervous. She looks like she’s about to be sick.

Her best pal, Phyllis Kirk drives her to Long Beach to visit Ann Dvorak (with some really nice rear screen projection).

As she’s leaving, Farley shows up, and Ann pushes him away, too, with her edginess. He spends the evening with her folks, playing cards with Dad and getting the lowdown on what’s been happening. He’s comfortable with her folks, and they are comfortable with him, brought together by their mutual concern over Ann. Again here, we see he’s a grownup, not a kid.

The phone rings. It’s Miss Dvorak. She doesn’t want Ann Blyth to come tonight because her husband’s home. Panic forces her anger, “Look, ya simply gotta stop her!”

Now Ann’s on a collision course, and we know it, but she doesn’t. It’s a great device for ratcheting up the tension. There’s no way that Farley and her folks, keeping vigil around the card table with the TV off (!), can reach Ann. She’s on her own.

Miss Dvorak’s husband, played by Ray Teal, so memorable as the obnoxious guy who got into a fight with Harold Russell in The Best Years of Our Livesand got slugged by Dana Andrews, here plays another bigmouth. He’s brought home a bunch of buddies and a few wives and girlfriends to play cards. The boys are playing poker. The girls are off by themselves, probably gossiping over canasta. Ann Dvorak, wanting desperately to head Ann Blyth off, nervously paces the porch, while husband Ray bellows for more beer.

“Get it, will ya? What’s the matter, you paralyzed or something?”

Miss Blyth arrives, stunned by the rabbit hutch of a home near the railroad tracks, the collection of strange people, the air heavy with cigarette and cigar smoke, by Ray’s playful leering at her, “I like ‘em young and cute like this,” and by her real mother pretending not to know her. Ann moves about like a zombie, while Miss Dvorak keeps up a steady stream of manic chatter, telling her husband and guests that this girl is the daughter of someone she used to know.

Having pulled back from her adopted family, Ann Blyth now discovers there is no connection, either, with her real mother. There is no place for her here. She belongs nowhere.

It’s a pitiable situation for both real mother and real daughter, and when the girls pull away in the expensive Cadillac convertible, disappearing in the dark, sultry night, Ann Dvorak stands on the porch watching them leave, dragging on her cigarette, tears in her eyes. She’s been through an emotional obstacle course.

Though we get the message that Ann is lucky to have been adopted by the “nice” people on the tree-lined street with a housekeeper, the story really isn’t so much about class. Farley Granger is working class, and he is a knight in shining armor. Mom and Dad have no problem with blue collar Farley. Actually, Dad is more unhappy about Ann’s friendship with Phyllis Kirk, who lives in a mansion with a butler, whose wealthy father buys her expensive presents.

Phyllis takes Ann back to her house to talk. Her father, a much-married playboy type, is not home, again. They sit at the bar in the living room, and Phyllis offers to freshen up Ann’s drink. No more is said about that, so we don’t really know if they have broken into dad’s liquor cabinet. Farley shows up to try to get Ann to go home, and they fight.

Farley is given “The Speech” in this movie: “All your life you’ve taken your folks and your home for granted, like any other kid. It’s very natural and nobody blames you, least of all your mother and father. But maybe now you won’t take it all for granted. If it makes that difference, I’d say it’s all to the good.”

This is the conclusion Ann will come to herself, eventually, but not yet. Farley leaves alone, unable to persuade her to go with him, and Ann finally gets her tail home around 3:00 in the morning, where Donald Cook has been waiting up for her. She mouths off to him, and he fires off a molar-loosening slap. Ten times more powerful than Joan Crawford’s slap in Mildred Pierce (1945), and Joan had a good arm. Miss Blyth is probably somewhere still rubbing her face right now.

Donald Cook had appeared with Ann earlier in one of the Universal teen musicals, Bowery to Broadway (1944), which we’ll discuss down the road. Our Very Own was his last film in a long career of mostly B-movies stretching back to the early 1930s, some theatre including Broadway, and TV claimed him for guest roles for the remainder of the 1950s, before he died in 1961.

The pacing of this movie is great. We slide from one encounter to another, one conflict on top of another, interspersed with quiet moments. Like the next morning, when Mom and Dad are seated alone at the dining room table, the heat of the night before dispersed and the eye of the hurricane settling on the house. It is cool and quiet. The kids are gone. They wonder how to bring Ann back into the fold.

Jane Wyatt offers, “It’s eighteen years of, well, this…love and care against a few anguished moments…” and as she speaks, the camera slowly pulls back (rather than moving in for the typical close-up), showing them in their setting, their home, their haven. There is much restraint in the cinematography, and some of the shots seem almost lyric in their meaning.

There are a couple very good mirror shots: one when Ann, speaking on the phone to her friend Phyllis, and in the mirror’s reflection we see Jessica Grayson and Jane Wyatt proudly fussing over the gown they’ve both made and gotten ready for their girl.

Another good mirror shot is when Phyllis Kirk sits before Ann’s vanity table and wistfully wishes that she might marry right away and have “scads of kids.” She doesn’t like being an only child. She's come over so she and Ann can dress together for the graduation. Her father will not attend the graduation ceremony because he’s going to a party. This, too, gives Ann something to think about.

By the way, check out Ann’s pedal pushers, and the way she and Phyllis Kirk wear their hair pulled back from their faces and tied in the back, the forerunner of the 1950s iconic ponytail.

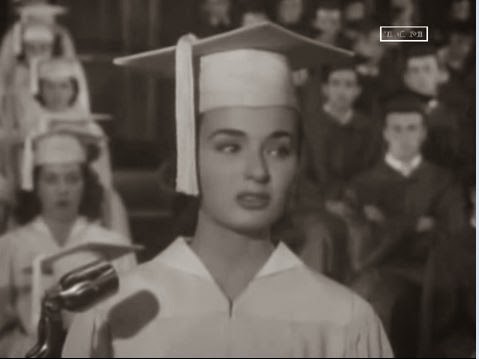

The biggest scene in the film is the splendid graduation scene, and the director wisely does not waste the occasion. He does not dismiss the importance of graduation by summarizing the event. He truly exploits this thunderous, rather Wagnerian display as one of our society’s greatest tribal rituals.

“Pomp and Circumstance,” so loud we can feel it in the belly, is performed by the high school orchestra. The school auditorium is filled to capacity. Ann’s family are there, having all arrived separately from their day at work, at school, at the hairdresser. Jessica Grayson is here, part of the family. Farley’s there, too, though seated alone in another section of the auditorium. We can imagine him rushing home after another sweaty day on somebody’s rooftop, grabbing a quick shower and putting on a jacket and tie to go to his girlfriend’s high school graduation.

The grads start filing in, shuffling in straight lines down the auditorium aisles, the boys and the girls (I wonder how many takes this required, how many times they “graduated”), and we spot Ann Blyth among them.

A nice touch, and rather poignant, that the director does not single her out as our star. She’s just one of the grads, looking a little lost as most grads do when they are the center of attention in a coming-of-age procession in medieval gown and mortarboard.

Her family spots her, but they can’t get her attention because she doesn't see them, even though she’s sneaking furtive glances around, looking for them. I love the universality to this, the common touch. We’ve all been there. We’ve been the grad looking for the familiar faces in the audience that belong to us, and we’ve been in the audience trying to make eye contact with our grad, anguished by the distance of several rows. It might as well be miles.

When it comes time for Ann to make the speech she’s been struggling with the entire movie, we really don’t know what she’s going to say. She has the typed paper in her hand, but it’s folded and she doesn’t refer to it, and though her delivery is poised—we can see she’s at last recovered her earlier composure—we don’t really know if she’s reciting what she has memorized, or if she’s talking off the top of her head. She blends the topic of her speech about citizenship with belonging to a family, and calls both a privilege.

It might seem that her acceptance of her adoption and her adopted family is sudden or wrapped up too quickly because she has been in such turmoil up to now, but I don’t think so. I think the script and the director play this one close to the vest, keeping the suspense to the very end. The emotional and psychological resolution has not been clumsily telegraphed to us beforehand. Ann has had such a rough time, we don’t know if she’s going to stand up there at the podium and say, “I just found out I was adopted and life stinks!” She could say anything, but her speech neatly exemplifies her discoveries made over the last few days. She has been learning many lessons, and she’s taken something away from each encounter—from her parents, from Ann Dvorak, from Farley, from Phyllis Kirk—to help her come to this sense of peace.

The only area where I think the film could have picked up a dropped thread was her relationship with Joan Evans, the instigator of the crisis. Instead, we have only a sisterly embrace outside in front of the school—another part of the graduation tribal ritual where the grad re-joins the family as a new person.

I would have liked there to be some private confession by Joan of her middle child woes, something to clue Ann in on what’s going on with her younger sister. But, in the end, siblings fight and make up and perhaps it doesn’t really matter why, it’s just family dynamics.

There is, however, a nicely symbolic reunion with her parents. When Ann hugs Jane Wyatt, buries her face in her neck and calls her “Mother,” we know Ann has just chosen Jane to be her mother, the way Jane chose her years before.

Then Donald Cook tenderly kisses Ann on the cheek he had slapped.

Most poignant, perhaps, is what happens next. Joan leaves the group and goes off with Martin Milner. Ann leaves the group and goes off with Farley. Dad looks down at Natalie and tells her not to be in a hurry to grow up.

The family is coming apart after all, just as Mother feared, but naturally, and though bittersweet, as Ann Dvorak says, “It’s just one of those things.”

Our Very Own was released on VHS many years ago, and is difficult to find. However, since this was a Samuel Goldwyn film, released through RKO—not one of Ann’s Universal outings—and because of those annoying omnipresent little “TCM” badges in the top right corner of the screen caps you see, I have hopes this might be an indication that a DVD release is in the offing. In the meantime, it has, obviously, been shown on TCM, and somebody recently put it up on YouTube. I won’t link to it because I don’t want to jinx it being taken down suddenly, but sneak over and have a look at this great movie when you’ve got the chance. Don't leave any fingerprints.

Have a look here at Mark’s fine blog Cin-Eater for another review of Our Very Own. It’s a great piece of writing that I love, and no surprise from the fella who also gives us the blog Where Danger Lives.

Have a listen here at a lovely version of the film’s theme song by the incomparable Sarah Vaughn.

Please visit the other blogs participating in CMBA’s Fabulous Films of the Fifties Blogathon.

Come back next Thursday when we have a look, or a listen, I should say, at a few of Ann’s guest radio appearances. A much shorter post. I swear.

******************************

Evening Courier (Prescott, Arizona), October 27, 1949, syndicated column by Gene Handsaker, p. 2.

Finstad, Suzanne. Natasha: The Biography of Natalie Wood (Three River Press, 2002).

Herald-Journal (Spartanburg, SC) November 27, 1949, syndicated column by Erskine Johnson, p. D4.

The Mount Washington News (New Hampshire) January 20, 1950, p. 38.

Reading (PA) Eagle, June 15, 1989, syndicated article by Jerry Buck, p. 27.

****************************

THANK YOU....to the following folks whose aid in gathering material for this series has been invaluable: EBH; Kevin Deany of Kevin's Movie Corner; Gerry Szymski of Westmont Movie Classics, Westmont, Illinois; and Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. of Thrilling Days of Yesteryear.

***************************

HELP!!!!!!!!!!

Now that I've got your attention: I'm still on the lookout for a movie called Katie Did It (1951) for this year-long series on the career of Ann Blyth. It seems to be a rare one. Please contact me on this blog or at my email: JacquelineTLynch@gmail.com if you know where I can lay my hands on this film. Am willing to buy or trade, or wash windows in exchange. Maybe not the windows part. But you know what I mean.

Also, if anybody has any of Ann's TV appearances, there's a few I'm missing from Switch, The Dick Powell Show, the Dennis Day Show (TV), the DuPont Show with June Allyson, This is Your Life, Lux Video Theatre. Also any video clips of her Oscar appearances. Release the hounds. And let me know, please.

***************************

HELP!!!!!!!!!!

Now that I've got your attention: I'm still on the lookout for a movie called Katie Did It (1951) for this year-long series on the career of Ann Blyth. It seems to be a rare one. Please contact me on this blog or at my email: JacquelineTLynch@gmail.com if you know where I can lay my hands on this film. Am willing to buy or trade, or wash windows in exchange. Maybe not the windows part. But you know what I mean.

Also, if anybody has any of Ann's TV appearances, there's a few I'm missing from Switch, The Dick Powell Show, the Dennis Day Show (TV), the DuPont Show with June Allyson, This is Your Life, Lux Video Theatre. Also any video clips of her Oscar appearances. Release the hounds. And let me know, please.

***************************

A new, collection of essays, some old, some new, from this blog titled Movies in Our Time: Hollywood Mimics and Mirrors the 20th Century will soon be issued in eBook as well as print. I hope to have it published later this month.

I’ll provide a free copy, either paperback or eBook or both if you wish, to classic film bloggers in exchange for an honest review. Just email me at JacquelineTLynch@gmail.com with your preference of format, your email address, and an address to mail the paperback (if that’s your preference). Thanks.

****************************

I was recently interviewed for the Springfield (Mass) Republican on my book on the Ames Manufacturing Company during the Civil War, and also online here.

No comments:

Post a Comment